What does blue sound like? Can painting be done with rhythm? And why is it that certain pieces of visual art hum, pulse, or vibrate off the wall? The connection between music and the visual arts is more than metaphor—it's an centuries-long dialogue between two mediums speaking the same language of emotion in two different tongues. When musicians and artists take from one another, it's not copying; it's resonance.

A Dialogue Without Words

Music and visual art both evade logic and enter directly into the nervous system. They don't need interpreting. You sense them. A progression of chords might be enough to leave you sobbing; a swooping curve of color might give you a shiver. These modes of communication stretch out for the same end: to express something inexpressible as words. In combination, the effect is overwhelming.

When Art Tried to Sound Like Music

In the early 20th century, abstract artist Wassily Kandinsky felt that shapes and colors possessed an immediate musicality. He wasn't the only one. Encouraged by the advent of modern music and developing scientific concepts regarding perception, artists started creating art that imitated the form of music.

Kandinsky, above all others, felt the direct connection of looking and listening. His paintings sometimes used a title such as "Composition" or "Improvisation," and he spoke of painting as "inner necessity"—the same compulsion that moves a composer to compose a symphony.

Later, the Bauhaus movement would apply this disintegration of distinctions between the aural and the visual to an interdisciplinary tension. And as jazz was at its peak in the 1950s, Jackson Pollock and Norman Lewis were already responding with their brushes to the syncopated, improvisational power of bebop.

Synesthesia and the Cross-Sensory Brain

The most literal links between music and art are synesthesia—a neuropsychological condition where stimulation of one sensory pathway triggers automatic, involuntary sensations in another. That is: some people literally see sounds as colors or hear colors as sounds.

David Hockney, Billy Joel, Kanye West, and Billie Eilish have all spoken about their synesthesia and how it influences the way they work. Color and music are not mutually exclusive categories for most of them. They're inextricably linked. Even for those who don't have synesthesia, the creative brain makes cross-sensory jumps.

A composer will call upon a sound to be "bright" or "cold." A painter might call a color scheme "loud." These are not figures of speech—rather, they convey how closely linked the two senses are within the brain.

Modern Crossovers

Now, the intersection of visual art and music has never been more obvious (and audible). Takashi Murakami's conceptual high-art collaborations with Kanye West (e.g., the cover of Graduation) are its most public incarnation to date. Artists have collaborated with artists such as Kehinde Wiley and Shepard Fairey on video installations, tour artwork, and merchandising.

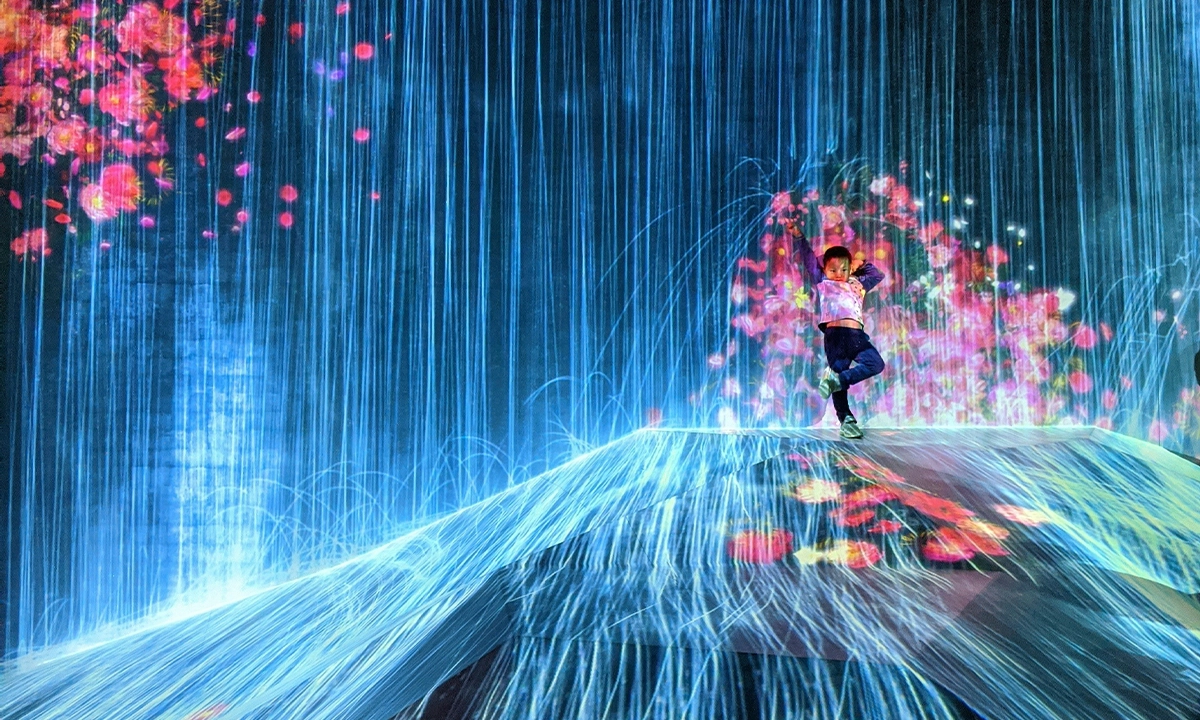

Even the museum itself has changed. Immersive exhibitions such as "Yayoi Kusama: Infinity Mirrors" or "Van Gogh Alive" apply painstakingly curated sound to navigate audiences through realms of vision. And on Instagram and TikTok, artists tend to accompany their visual practice with sound in an attempt to construct narrative and atmosphere.

The Emotional Architecture of Both

Both music and visual art are structure-based to convey emotion. Layering, contrast, repetition, harmony, and dissonance aren't technicalities of music—rules govern the construction of a painting as well.

Psychologically, they also strike the same nerve centers. Both art and music activate the amygdala (the emotional center of the brain) and the prefrontal cortex (which processes meaning and memory). When you feel moved by a song that resonates with you, or by a painting that grabs at something deep within you, your brain lights up in remarkably similar fashion.

From the Artist's Point of View

Being a visual artist with a strong affinity for sound, I find that this particular song of music will dictate the mood of a piece in progress. A slow ambient song will guide the making of soft flowing lines. A raw bass will evoke strong contrast and heavy layers.

I'll begin with color sometimes, and then out of the palette of color, a soundtrack will come. Reversed other times, music first, and I am translating tempo into brushstrokes. Influence isn't what it is, exactly; it's translation—like the two media are versions of the same story, told twice.

Why It Matters

In this hyper-stimulated world, stimulating multiple senses simultaneously isn't distracting—it's a richer calling. Where music and visual art cross over, it's a reminder that creativity is not isolated. It's fluid. It moves. It changes.

We don't simply hear music. We sense it. We don't simply view paintings. We breathe them in. And sometimes the greatest art breakthroughs occur when we release the need to distinguish between those two realities.

So the next time you're in front of a painting, ask: what does this sound like? And when you hear some music that leaves you frozen in place, ask: what colors do I find in that sound?

Your brain likely already knows. You just have to see—and hear.

.svg)